Sonic Landscapes

Kimbal Bumstead

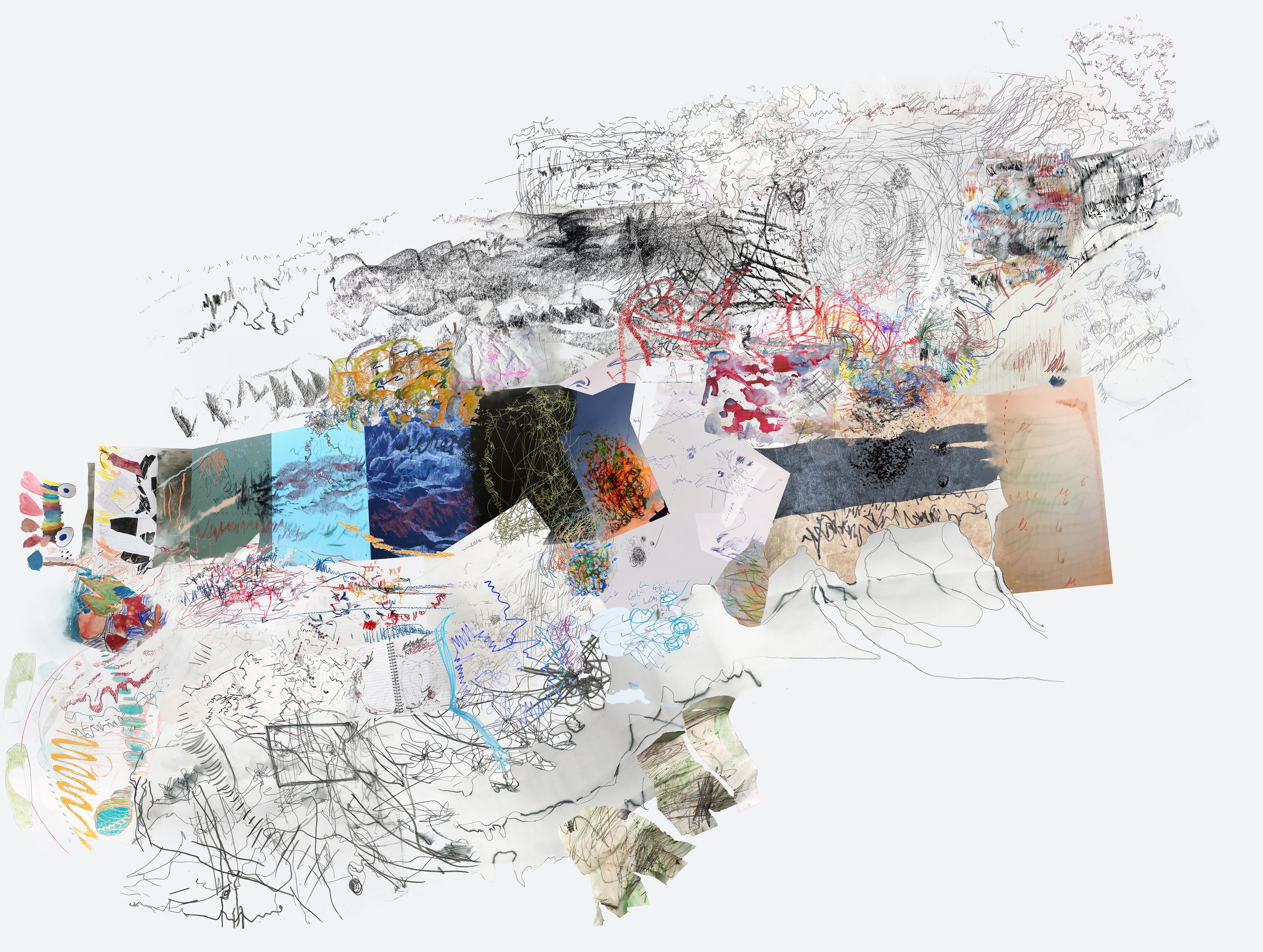

The map above is part of Sonic Landscapes, a participatory art project which explores drawing as a tool to tune into and map the experience of everyday environmental sound. Due to pandemic restrictions at the time, I presented this artwork virtually as a webpage with a zoomable image of the collage above and a button that when pressed, played the soundtrack that accompanied it. Visitors could zoom into and drag the image to see details in the drawings, in a similar way to an online map such as Google Maps, while becoming immersed in the soundtrack.

Sonic Landscapes builds on my previous work exploring the notion of ‘embodied drawing’, which investigates the physicality of drawing as a way of mapping the body’s physical and emotional connection to the space it is in.[1] While my previous projects have focused on the sense of touch, for this work, which was part of my Artist Residency at Basement Arts Project in Leeds (UK) in April 2021, I decided to work with the sensory experience of sound.

Sonic Landscapes comprises two main aspects: a mapping process to generate materials and the two artworks I created using those materials. The mapping process was carried out via an open call on social media. I asked for people to contribute drawings made in response to sounds in their local environment. I also asked for an audio recording of the ambient sound they drew. I instructed participants to draw with their eyes closed in order to listen for, and consequently capture on paper, the qualities, textures and rhythms they heard. To encourage participants to move away from representational drawing as much as possible, I suggested that they should not name or identify the source of the sound. For instance, if they heard birdsong, they should focus on the quality of the sound itself – hard, soft, loud, rasping or rounded etc – and mark their perception of those qualities, rather than drawing what produced the sound. The action of drawing, and the point of contact between drawing tool and paper, was intended as a tool to pinpoint specific sounds and focus attention towards their qualities.

Over the course of one month, I gathered images of people’s sound drawings and their audio recordings. Each drawing and recording differed in style and character, both in terms of the actual marks, but also in in terms of the varieties of paper and different drawing materials used. I used the collected material to create two artworks: a digital collage with an accompanying soundtrack, and a live sound performance with an accompanying video.

While making the collage, I imagined that I was creating, and mapping, an ever-evolving landscape. Each new submission allowed new spaces to come into existence and the imaginary landscape to evolve. I incorporated new drawings into the existing collage, by either attaching them to the edges of what was already there or by layering them, semi-transparently, on top of the previous images so that they intertwined. I worked with the marks in the drawings to make them appear as if they could be representations of geographical features or urban infrastructure; lines which could be paths to travel along.

My approach was intuitive and inspired by my painting practice; I connected lines and shapes from one drawing to another so that they flowed into each other to create dynamism in the composition.

Alongside the collage, I created an audio piece using the recorded sounds submitted, which was intended as an immersive guide for an imagined journey through the places depicted. The soundtrack fades in and out of geographically diverse places; urban sounds meet sounds of natural environments, sounds of people going about their lives, voices, footsteps and excerpts from TV and radio, are interspersed with rhythmic clicks, pops and scratches that were present in some of the recordings. Some of the recordings are unprocessed, whereas others were modified to obtain a musical atmosphere by, for example, looping rhythmic sections and/or filtering resonant sections to create melodic elements.

The soundtrack itself has a somewhat linear narrative in that it has a start, a middle and an end, and it runs for a set length of time; in other words, it follows a specific line. It is unclear however, which line, or lines, in the collage, the soundtrack may be following. There is no obvious correlation between the sounds and the drawings, so it is up to the viewer to determine the route of the journey and make their own connections between drawn marks and the places they may or may not signify.

While working on this project, I thought of the similarities between my piece and a 17th Century Japanese woodcut map I had seen an image of some years before at the National Diet Library in Tokyo. The Tokaido Bunken Ezu[2] is a pictorial map of the road that travellers would have taken to go from Edo to Kyoto along the ‘Eastern Sea Road’. In contrast to contemporary road maps which present a network of routes crossing a given space, the Tokaido Bunken Ezu presents only a singular linear route from A to B, flattened on to a horizontal plane. The map is illustrated with drawings of landmarks and potential encounters that one might find along the way, as if telling the story of a journey. Both in the case of my work and the Japanese woodcut, viewers can ‘travel along’, as it were, on the mapmaker’s journey, via their own imaginations.

My second artwork of the project aimed to move away from the linear structure I had created towards a more fluid perspective. Rather than presenting just one journey, or story, I wanted to reflect on the nature of the collage as an assemblage of multiple experiences, interpretations, and possibilities. To this end, I developed a live performance of the sound piece which allowed for the audio clips to be assembled and modified differently each time it was performed. The live performance includes a video of a journey through the collage, which pans around the image travelling along the lines in the drawings. In this piece, the role of the linear and the non-linear is reversed, with the image becoming linear and the soundtrack non-linear. I manipulated the sound in response to what I saw on the screen, using MIDI controllers to modify certain parameters and using the video as a kind of score. I cropped, stretched, and looped clips, changed their pitch, and added effects such as delay and reverb, considering them as raw materials to create a musical experience. I performed the piece at AMP studios, London, as part of Pri’s Art Salon event in July 2021, and also virtually via a video link as part of Ginseng International Performance Art Exhibition organised by Charcoal Foundation in Delhi, India in November 2021.

A place may sound different on different occasions and in different contexts; indeed, if one was to make a one-minute recording in a given location at different times throughout the day, the outcome will change dramatically depending on what is going on at the given time. In a similar fashion, the perception and experience of ambient sound may vary considerably both among and within listeners. This project explored how drawing can be used to record such multiple and subjective experiences of sound, and consequently, how those recorded sensations could become fluid maps which reimagine the spaces they came from. I believe that, at least to a certain degree, all maps offer the potential to travel into the imagination; maps of places we know can recall memories or experiences we have had in those places while a map of a place we do not know can prompt us to imagine what that place might be like. As such, my project reflects on the entangled relationship between maps and the imagination, and how maps can help us to travel, even without going anywhere.

All aspects of this project, from drawing sound, to using sonic and visual materials to re-imagine places as artworks, to the experience of viewers and listeners, involves interpretation. As with any audiovisual experience, what someone sees or hears, or what it makes them think about is unpredictable, and I think that this is also true for maps. Maps may appear as static representations of places, but the memories or imaginings that maps might evoke for people is fluid and subjective. While the project I have described does not necessarily help to contribute specific understanding of specific places, the process of attempting to capture something which is essentially impossible to capture (i.e. sensory experience), may help those who attempt to capture it (i.e. the participants), gain a new perspective of the place they are in. Likewise, we, the artists, viewers, map makers and map readers are reminded that there are always multiple ways of experiencing places and the representations of places.

A zoomable version of the map, the audio track, and video extracts of the live performance can all be found at www.kimbalbumstead.com/projects/soniclandscapes.

Notes

[1] See Unmapping Space: Lines, Smudges and Stories, Chapter 15 in New Directions in Radical Cartography, Rowman and Littlefield Publishers, 2021

[2] Ochikochi Dōin, A. 1. C. & Hishikawa, M. Tōkaidō Bunken Ezu. [Japan: s.n., 17--?] [Map] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2002531180/